Java 16 is around the corner, so there’s no better time than now for learning more about the features which the new version will bring. After exploring the support for Unix domain sockets a while ago, I’ve lately been really curious about the incubating Vector API, as defined by JEP 338, developed under the umbrella of Project Panama, which aims at "interconnecting JVM and native code".

Vectors?!?

Of course this is not about renewing the ancient Java collection types like java.util.Vector

(<insert some pun about this here>),

but rather about an API which lets Java developers take advantage of the vector calculation capabilities you can find in most CPUs these days.

Now I’m by no means an expert on low-level programming leveraging specific CPU instructions,

but exactly that’s why I hope to make the case with this post that the new Vector API makes these capabilities approachable to a wide audience of Java programmers.

What’s SIMD Anyways?

Before diving into a specific example, it’s worth pointing out why that API is so interesting, and what it could be used for. In a nutshell, CPU architectures like x86 or AArch64 provide extensions to their instruction sets which allow you to apply a single operation to multiple data items at once (SIMD — single instruction, multiple data). If a specific computing problem can be solved using an algorithm that lends itself to such parallelization, substantial performance improvements can be gained. Examples for such SIMD instruction set extensions include SSE and AVX for x64, and Neon of AArch64 (Arm).

As such, they complement other means of compute parallelization: scaling out across multiple machines which collaborate in a cluster, and multi-threaded programming. Unlike these though, vectorized computations are done within the scope of an individual method, e.g. operating on multiple elements of an array at once.

So far, there was no way for Java developers to directly work with such SIMD instructions. While you can use SIMD intrinsics in languages closer to the metal such as C/C++, no such option exists in Java so far. Note this doesn’t mean Java wouldn’t take advantage of SIMD at all: the JIT compiler can auto-vectorize code in specific situations, i.e. transforming code from a loop into vectorized code. Whether that’s possible or not isn’t easy to determine, though; small changes to a loop which the compiler was able to vectorize before, may lead to scalar execution, resulting in a performance regression.

JEP 338 aims to improve this situation: introducing a portable vector computation API, it allows Java developers to benefit from SIMD execution by means of explicitly vectorized algorithms. Unlike C/C++ style intrinsics, this API will be mapped automatically by the C2 JIT compiler to the corresponding instruction set of the underlying platform, falling back to scalar execution if the platform doesn’t provide the required capabilities. A pretty sweet deal, if you ask me!

Now, why would you be interested in this? Doesn’t "vector calculation" sound an awful lot like mathematics-heavy, low-level algorithms, which you don’t tend to find that much in your typical Java enterprise applications? I’d say, yes and no. Indeed it may not be that beneficial for say a CRUD application copying some data from left to right. But there are many interesting applications in areas like image processing, AI, parsing, (SIMD-based JSON parsing being a prominently discussed example), text processing, data type conversions, and many others. In that regard, I’d expect that JEP 338 will pave the path for using Java in many interesting use cases, where it may not be the first choice today.

Vectorizing FizzBuzz

To see how the Vector API can help with improving the performance of some calculation, let’s consider FizzBuzz. Originally, FizzBuzz is a game to help teaching children division; but interestingly, it also serves as entry-level interview question for hiring software engineers in some places. In any case, it’s a nice example for exploring how some calculation can benefit from vectorization. The rules of FizzBuzz are simple:

-

Numbers are counted and printed out: 1, 2, 3, …

-

If a number if divisible by 3, instead of printing the number, print "Fizz"

-

If a number if divisible by 5, print "Buzz"

-

If a number if divisible by 3 and 5, print "FizzBuzz"

As the Vector API concerns itself with numeric values instead of strings, rather than "Fizz", "Buzz", and "FizzBuzz", we’re going to emit -1, -2, and -3, respectively. The input of the program will be an array with the numbers from 1 … 256, the output an array with the FizzBuzz sequence:

1

1, 2, -1, 4, -2, -1, 7, 8, -1, -2, 11, -1, 13, 14, -3, 16, ...

The task is easily solved using a plain for loop processing scalar values one by one:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

private static final int FIZZ = -1;

private static final int BUZZ = -2;

private static final int FIZZ_BUZZ = -3;

public int[] scalarFizzBuzz(int[] values) {

int[] result = new int[values.length];

for (int i = 0; i < values.length; i++) {

int value = values[i];

if (value % 3 == 0) {

if (value % 5 == 0) { (1)

result[i] = FIZZ_BUZZ;

}

else {

result[i] = FIZZ; (2)

}

}

else if (value % 5 == 0) {

result[i] = BUZZ; (3)

}

else {

result[i] = value; (4)

}

}

return result;

}

| 1 | The current number is divisible by 3 and 5: emit FIZZ_BUZZ (-3) |

| 2 | The current number is divisible by 3: emit FIZZ (-1) |

| 3 | The current number is divisible by 5: emit BUZZ (-2) |

| 4 | The current number is divisible by neither 3 nor 5: emit the number itself |

As a baseline, this implementation can be executed ~2.2M times per second in a simple JMH benchmark running on my Macbook Pro 2019, with a 2.6 GHz 6-Core Intel Core i7 CPU:

1

2

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2204774,792 ± 76581,374 ops/s

Now let’s see how this calculation could be vectorized and what performance improvements can be gained by doing so.

When looking at the incubating Vector API,

you may be overwhelmed at first by its large API surface.

But it’s becoming manageable once you realize that all the types like IntVector, LongVector, etc. essentially expose the same set of methods,

only specific for each of the supported data types

(and indeed, as per the JavaDoc, all these classes were not hand-written by some poor soul, but generated, from some sort of parameterized template supposedly).

Amongst the plethora of API methods, there is no modulo operation, though

(which makes sense, as for instance there isn’t such instruction in any of the x86 SIMD extensions).

So what could we do to solve the FizzBuzz task?

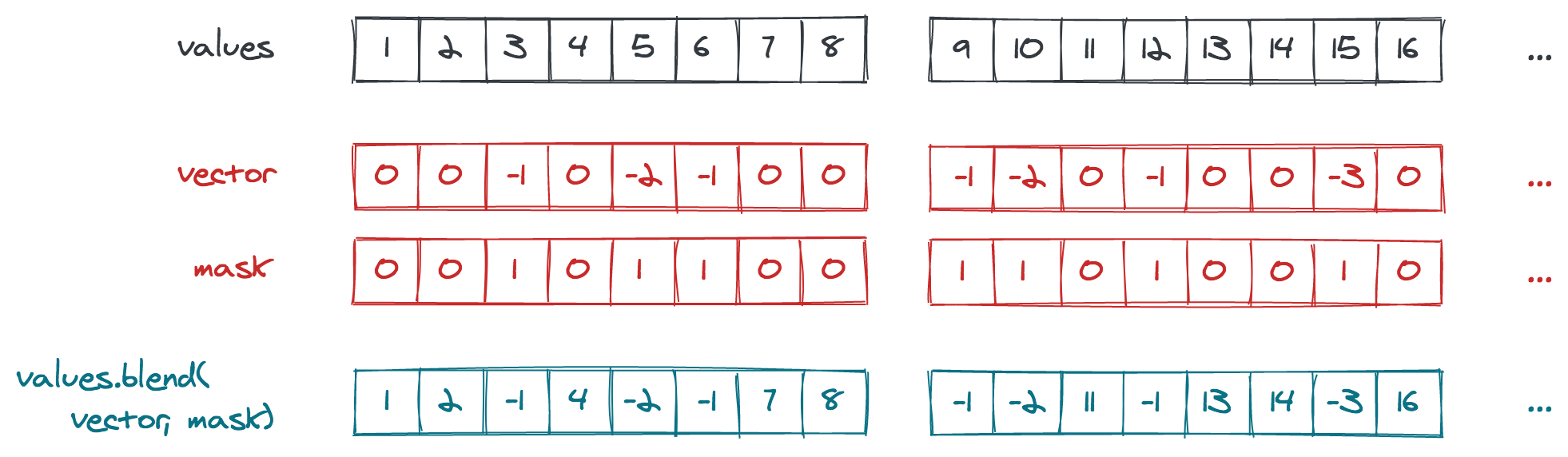

After skimming through the API for some time, the method blend(Vector<Integer> v, VectorMask<Integer> m) caught my attention:

Replaces selected lanes of this vector with corresponding lanes from a second input vector under the control of a mask. […]

For any lane set in the mask, the new lane value is taken from the second input vector, and replaces whatever value was in the that lane of this vector.

For any lane unset in the mask, the replacement is suppressed and this vector retains the original value stored in that lane.

This sounds pretty useful;

The pattern of expected -1, -2, and -3 values repeats every 15 input values.

So we can "pre-calculate" that pattern once and persist it in form of vectors and masks for the blend() method.

While stepping through the input array,

the right vector and mask are obtained based on the current position and are used with blend() in order to mark the values divisible by 3, 5, and 15

(another option could be min(Vector<Integer> v),

but I decided against it, as we’d need some magic value for representing those numbers which should be emitted as-is).

Here is a visualization of the approach, assuming a vector length of eight elements ("lanes"):

So let’s see how we can implement this using the Vector API. The mask and second input vector repeat every 120 elements (least common multiple of 8 and 15), so 15 masks and vectors need to be determined. They can be created like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

public class FizzBuzz {

private static final VectorSpecies<Integer> SPECIES =

IntVector.SPECIES_256; (1)

private final List<VectorMask<Integer>> resultMasks =

new ArrayList<>(15);

private final IntVector[] resultVectors = new IntVector[15];

public FizzBuzz() {

List<VectorMask<Integer>> threes = Arrays.asList( (2)

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b00100100),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b01001001),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b10010010)

);

List<VectorMask<Integer>> fives = Arrays.asList( (3)

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b00010000),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b01000010),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b00001000),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b00100001),

VectorMask.<Integer>fromLong(SPECIES, 0b10000100)

);

for(int i = 0; i < 15; i++) { (4)

VectorMask<Integer> threeMask = threes.get(i%3);

VectorMask<Integer> fiveMask = fives.get(i%5);

resultMasks.add(threeMask.or(fiveMask)); (5)

resultVectors[i] = IntVector.zero(SPECIES) (6)

.blend(FIZZ, threeMask)

.blend(BUZZ, fiveMask)

.blend(FIZZ_BUZZ, threeMask.and(fiveMask));

}

}

}

| 1 | A vector species describes the combination of an vector element type (in this case Integer) and a vector shape (in this case 256 bit); i.e. here we’re going to deal with vectors that hold 8 32 bit int values |

| 2 | Vector masks describing the numbers divisible by three (read the bit values from right to left) |

| 3 | Vector masks describing the numbers divisible by five |

| 4 | Let’s create the fifteen required result masks and vectors |

| 5 | A value in the output array should be set to another value if it’s divisible by three or five |

| 6 | Set the value to -1, -2, or -3, depending on whether its divisible by three, five, or fifteen, respectively; otherwise set it to the corresponding value from the input array |

With this infrastructure in place, we can implement the actual method for calculating the FizzBuzz values for an arbitrarily long input array:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

public int[] simdFizzBuzz(int[] values) {

int[] result = new int[values.length];

int i = 0;

int upperBound = SPECIES.loopBound(values.length); (1)

for (; i < upperBound; i += SPECIES.length()) { (2)

IntVector chunk = IntVector.fromArray(SPECIES, values, i); (3)

int maskIdx = (i/SPECIES.length())%15; (4)

IntVector fizzBuzz = chunk.blend(resultValues[maskIdx],

resultMasks[maskIdx]); (5)

fizzBuzz.intoArray(result, i); (6)

}

for (; i < values.length; i++) { (7)

int value = values[i];

if (value % 3 == 0) {

if (value % 5 == 0) {

result[i] = FIZZ_BUZZ;

}

else {

result[i] = FIZZ;

}

}

else if (value % 5 == 0) {

result[i] = BUZZ;

}

else {

result[i] = value;

}

}

return result;

}

| 1 | determine the maximum index in the array that’s divisible by the species length; e.g. if the input array is 100 elements long, that’d be 96 in the case of vectors with eight elements each |

| 2 | Iterate through the input array in steps of the vector length |

| 3 | Load the current chunk of the input array into an IntVector |

| 4 | Obtain the index of the right result vector and mask |

| 5 | Determine the FizzBuzz numbers for the current chunk (i.e. that’s the actual SIMD instruction, processing all eight elements of the current chunk at once) |

| 6 | Copy the result values at the right index into the result array |

| 7 | Process any remainder (e.g. the last four remaining elements in case of an input array with 100 elements) using the traditional scalar approach, as those values couldn’t fill up another vector instance |

To reiterate what’s happening here: instead of processing the values of the input array one by one, they are processed in chunks of eight elements each by means of the blend() vector operation,

which can be mapped to an equivalent SIMD instruction of the CPU.

In case the input array doesn’t have a length that’s a multiple of the vector length,

the remainder is processed in the traditional scalar way.

The resulting duplication of the logic seems a bit inelegant, we’ll discuss in a bit what can be done about that.

For now, let’s see whether our efforts pay off; i.e. is this vectorized approach actually faster then the basic scalar implementation? Turns out it is! Here are the numbers I get from JMH on my machine, showing through-put increasing by factor 3:

1

2

3

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2204774,792 ± 76581,374 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 6748723,261 ± 34725,507 ops/s

Is there anything that could be further improved? I’m pretty sure, but as said I’m not an expert here, so I’ll leave it to smarter folks to point out more efficient implementations in the comments. One thing I figured is that the division and modulo operation for obtaining the current mask index isn’t ideal. Keeping a separate loop variable that’s reset to 0 after reaching 15 proved to be quite a bit faster:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public int[] simdFizzBuzz(int[] values) {

int[] result = new int[values.length];

int i = 0;

int j = 0;

int upperBound = SPECIES.loopBound(values.length);

for (; i < upperBound; i += SPECIES.length()) {

IntVector chunk = IntVector.fromArray(SPECIES, values, i);

IntVector fizzBuzz = chunk.blend(resultValues[j], resultMasks[j]);

fizzBuzz.intoArray(result, i);

j++;

if (j == 15) {

j = 0;

}

}

// processing of remainder...

}

1

2

3

4

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2204774,792 ± 76581,374 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 6748723,261 ± 34725,507 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzSeparateMaskIndex 256 thrpt 5 8830433,250 ± 69955,161 ops/s

This makes for another nice improvement, yielding 4x the throughput of the original scalar implementation. Now, to make this a true apple-to-apple comparison, a mask-based approach can also be applied to the purely scalar implementation, only that each value needs to be looked up individually:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

private int[] serialMask = new int[] {0, 0, -1, 0, -2,

-1, 0, 0, -1, -10,

0, -1, 0, 0, -3};

public int[] serialFizzBuzzMasked(int[] values) {

int[] result = new int[values.length];

int j = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < values.length; i++) {

int res = serialMask[j];

result[i] = res == 0 ? values[i] : res;

j++;

if (j == 15) {

j = 0;

}

}

return result;

}

Indeed, this implementation is quite a bit better than the original one, but still the SIMD-based approach is more than twice as fast:

1

2

3

4

5

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2204774,792 ± 76581,374 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzzMasked 256 thrpt 5 4156751,424 ± 23668,949 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 6748723,261 ± 34725,507 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzSeparateMaskIndex 256 thrpt 5 8830433,250 ± 69955,161 ops/s

Examining the Native Code

This all is pretty cool, but can we trust that under the hood things actually happen the way we expect them to happen? In order to verify that, let’s take a look at the native assembly code that gets produced by the JIT compiler for this implementation. This requires you to run the JVM with the hsdis plug-in; see this post for instructions on how to build and install hsdis. Let’s create a simple main class which executes the method in question in a loop, so to make sure the method actually gets JIT-compiled:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class Main {

public static int[] blackhole;

public static void main(String[] args) {

FizzBuzz fizzBuzz = new FizzBuzz();

var values = IntStream.range(1, 257).toArray();

for(int i = 0; i < 5_000_000; i++) {

blackhole = fizzBuzz.simdFizzBuzz(values);

}

}

}

Run the program, enabling the output of the assembly, and piping its output into a log file:

1

2

3

4

5

java -XX:+UnlockDiagnosticVMOptions \

-XX:+PrintAssembly -XX:+LogCompilation \

--add-modules=jdk.incubator.vector \

--class-path target/classes \

dev.morling.demos.simdfizzbuzz.Main > fizzbuzz.log

Open the fizzbuzz.log file and look for the C2-compiled nmethod block of the simdFizzBuzz method.

Somewhere within the method’s native code, you should find the vpblendvb instruction

(output slightly adjusted for better readability):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

...

=========================== C2-compiled nmethod ============================

--------------------------------- Assembly ---------------------------------

Compiled method (c2) ... dev.morling.demos.simdfizzbuzz.FizzBuzz:: ↩

simdFizzBuzz (161 bytes)

...

0x000000011895e18d: vpmovsxbd %xmm7,%ymm7 ↩

;*invokestatic store {reexecute=0 rethrow=0 return_oop=0}

; - jdk.incubator.vector.IntVector::intoArray@42 (line 2962)

; - dev.morling.demos.simdfizzbuzz.FizzBuzz::simdFizzBuzz@76 (line 92)

0x000000011895e192: vpblendvb %ymm7,%ymm5,%ymm8,%ymm0 ↩

;*invokestatic blend {reexecute=0 rethrow=0 return_oop=0}

; - jdk.incubator.vector.IntVector::blendTemplate@26 (line 1895)

; - jdk.incubator.vector.Int256Vector::blend@11 (line 376)

; - jdk.incubator.vector.Int256Vector::blend@3 (line 41)

; - dev.morling.demos.simdfizzbuzz.FizzBuzz::simdFizzBuzz@67 (line 91)

...

vpblendvb is part of the x86 AVX2 instruction set and "conditionally copies byte elements from the source operand (second operand) to the destination operand (first operand) depending on mask bits defined in the implicit third register argument",

as such exactly corresponding to the blend() method in the JEP 338 API.

One detail not quite clear to me is why vpmovsxbd for copying the results into the output array

(the intoArray() call) shows up before vpblendvb.

If you happen to know the reason for this, I’d love to hear from you and learn about this.

Avoiding Scalar Processing of Tail Elements

Let’s get back to the scalar processing of the potential remainder of the input array. This feels a bit "un-DRY", as it requires the algorithm to be implemented twice, once vectorized and once in a scalar way.

The Vector API recognizes the desire for avoiding this duplication and provides masked versions of all the required operations, so that during the last iteration no access beyond the array length will happen. Using this approach, the SIMD FizzBuzz method looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public int[] simdFizzBuzzMasked(int[] values) {

int[] result = new int[values.length];

int j = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < values.length; i += SPECIES.length()) {

var mask = SPECIES.indexInRange(i, values.length); (1)

var chunk = IntVector.fromArray(SPECIES, values, i, mask); (2)

var fizzBuzz = chunk.blend(resultValues[j], resultMasks.get(j));

fizzBuzz.intoArray(result, i, mask); (2)

j++;

if (j == 15) {

j = 0;

}

}

return result;

}

| 1 | Obtain a mask which, during the last iteration, will have bits for those lanes unset, which are larger than the last encountered multiple of the vector length |

| 2 | Perform the same operations as above, but using the mask to prevent any access beyond the array length |

The implementation looks quite a bit nicer than the version with the explicit scalar processing of the remainder portion. But the impact on throughput is significant, the result is quite a disappointing:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2204774,792 ± 76581,374 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzzMasked 256 thrpt 5 4156751,424 ± 23668,949 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 6748723,261 ± 34725,507 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzSeparateMaskIndex 256 thrpt 5 8830433,250 ± 69955,161 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzMasked 256 thrpt 5 1204128,029 ± 5556,553 ops/s

In its current form, this approach is even slower than the pure scalar implementation. It remains to be seen whether and how performance gets improved here, as the Vector API matures. Ideally, the mask would have to be only applied during the very last iteration. This is something we either could do ourselves — re-introducing some special remainder handling, albeit less different from the core implementation than with the pure scalar approach discussed above — or perhaps even the compiler itself may be able to apply such transformation.

One important take-away from this is that a SIMD-based approach does not necessarily have to be faster than a scalar one. So every algorithmic adjustment should be validated with a corresponding benchmark, before drawing any conclusions. Speaking of which, I also ran the benchmark on that shiny new Mac Mini M1 (i.e. an AArch64-based machine) that found its way to my desk recently, and numbers are, mh, interesting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Benchmark (arrayLength) Mode Cnt Score Error Units

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 2717990,097 ± 4203,628 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.scalarFizzBuzzMasked 256 thrpt 5 5750402,582 ± 2479,462 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzz 256 thrpt 5 1297631,404 ± 15613,288 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzMasked 256 thrpt 5 374313,033 ± 2219,940 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzMasksInArray 256 thrpt 5 1316375,073 ± 1178,704 ops/s

FizzBuzzBenchmark.simdFizzBuzzSeparateMaskIndex 256 thrpt 5 998979,324 ± 69997,361 ops/s

The scalar implementation on the M1 out-performs the x86 MacBook Pro by quite a bit, but SIMD numbers are significantly lower.

I haven’t checked the assembly code, but solely based on the figures, my guess is that the JEP 338 implementation in the current JDK 16 builds does not yet support AArch64, and the API falls back to scalar execution.

Here it would be nice to have some method in the API which reveals whether SIMD support is provided by the current platform or not,

as e.g. done by .NET with its Vector.IsHardwareAccelerated() method.

Update, March 9th: After asking about this on the panama-dev mailing list, Ningsheng Jian from Arm explained that the AArch64 NEON instruction set has a maximum hardware vector size of 128 bits;

hence the Vector API is transparently falling back to the Java implementation in our case of using 256 bits.

By passing the -XX:+PrintIntrinsics flag you can inspect which API calls get intrinsified (i.e. executed via corresponding hardware instructions) and which ones not.

When running the main class from above with this option, we get the relevant information

(output slightly adjusted for better readability):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@ 31 jdk.internal.vm.vector.VectorSupport::load (38 bytes) ↩

failed to inline (intrinsic)

...

@ 26 jdk.internal.vm.vector.VectorSupport::blend (38 bytes) ↩

failed to inline (intrinsic)

...

@ 42 jdk.internal.vm.vector.VectorSupport::store (38 bytes) ↩

failed to inline (intrinsic)

** not supported: arity=0 op=load vlen=8 etype=int ismask=no

** not supported: arity=2 op=blend vlen=8 etype=int ismask=useload

** not supported: arity=1 op=store vlen=8 etype=int ismask=no

Fun fact: during the entire benchmark runtime of 10 min the fan of the Mac Mini was barely to hear, if at all. Definitely a very exciting platform, and I’m looking forward to doing more Java experiments on it soon.

Wrap-Up

Am I suggesting you should go and implement your next FizzBuzz using SIMD? Of course not, FizzBuzz just served as an example here for exploring how a well-known "problem" can be solved more efficiently via the new Java Vector API (at the cost of increased complexity in the code), also without being a seasoned systems programmer. On the other hand, it may make an impression during your next job interview ;)

If you want to get started with your own experiments around the Vector API and SIMD,

install a current JDK 16 RC (release candidate) build and grab the SIMD FizzBuzz example from this GitHub repo.

A nice twist to explore would for instance be using ShortVector instead of IntVector

(allowing to put 16 values into 256-bit vector),

running the benchmark on machines with the AVX-512 extension

(e.g. via the C5 instance type on AWS EC2),

or both :)

Apart from the JEP document itself, there isn’t too much info out yet about the Vector API; a great starting point are the "vector" tagged posts on the blog of Richard Startin. Another inspirational resource is August Nagro’s project for vectorized UTF-8 validation based on a paper by John Keiser and Daniel Lemire. Kishor Kharbas and Paul Sandoz did a talk about the Vector API at CodeOne a while ago.

Taking a step back, it’s hard to overstate the impact which the Vector API potentially will have on the Java platform. Providing SIMD capabilities in a rather easy-to-use, portable way, without having to rely on CPU instruction set specific intrinsics, may result in nothing less than a "democratization of SIMD", making these powerful means of parallelizing computations available to a much larger developer audience.

Also the JDK class library itself may benefit from the Vector API; while JDK authors — unlike Java application developers — already have the JVM intrinsics mechanism at their disposal, the new API will "make prototyping easier, and broaden what might be economical to consider", as pointed out by Claes Redestad.

But nothing in life is free, and code will have to be restructured or even re-written in order to benefit from this. Some problems lend themselves better than others to SIMD-style processing, and only time will tell in which areas the new API will be adopted. As said above, use cases like image processing and AI can benefit from SIMD a lot, due to the nature of the underlying calculations. Also specific data store operations can be sped up significantly using SIMD instructions; so my personal hope is that the Vector API can contribute to making Java an attractive choice for such applications, which previously were not considered a sweet spot for the Java platform.

As such, I can’t think of many recent Java API additions which may prove as influential as the Vector API.