For building a system of distributed services, one concept I think is very valuable to keep in mind is what I call the synchrony budget: as much as possible, a service should minimize the number of synchronous requests which it makes to other services.

The reasoning behind this is two-fold: synchronous calls are costly. The more synchronous requests you are doing, the longer it will take to process inbound requests to your own service; users don’t like to wait and might decide to take their business elsewhere if things take too long. Secondly, synchronous requests impact the availability of your service, because all the invoked services must be up and running in order for your service to work. The more services you rely on in a synchronous manner, the lower the availability of your service will be.

Synchronous calls are tools that can help assure consistency, but by design they block progression until complete. In that sense, the idea of the synchrony budget is not about a literal budget which you can spend, but rather about being mindful how you implement communication flows between services: as asynchronous as possible, as synchronous as necessary.

Let’s make things a bit more tangible by looking at an example. Consider an e-commerce website where users can place purchase orders. When an order comes in, the order entry service needs to interact with a couple of other services in order to process that order:

-

a payment service for processing the payment of the customer

-

an inventory service for allocating stock of the purchased item

-

a shipment service for triggering the fulfillment of the order

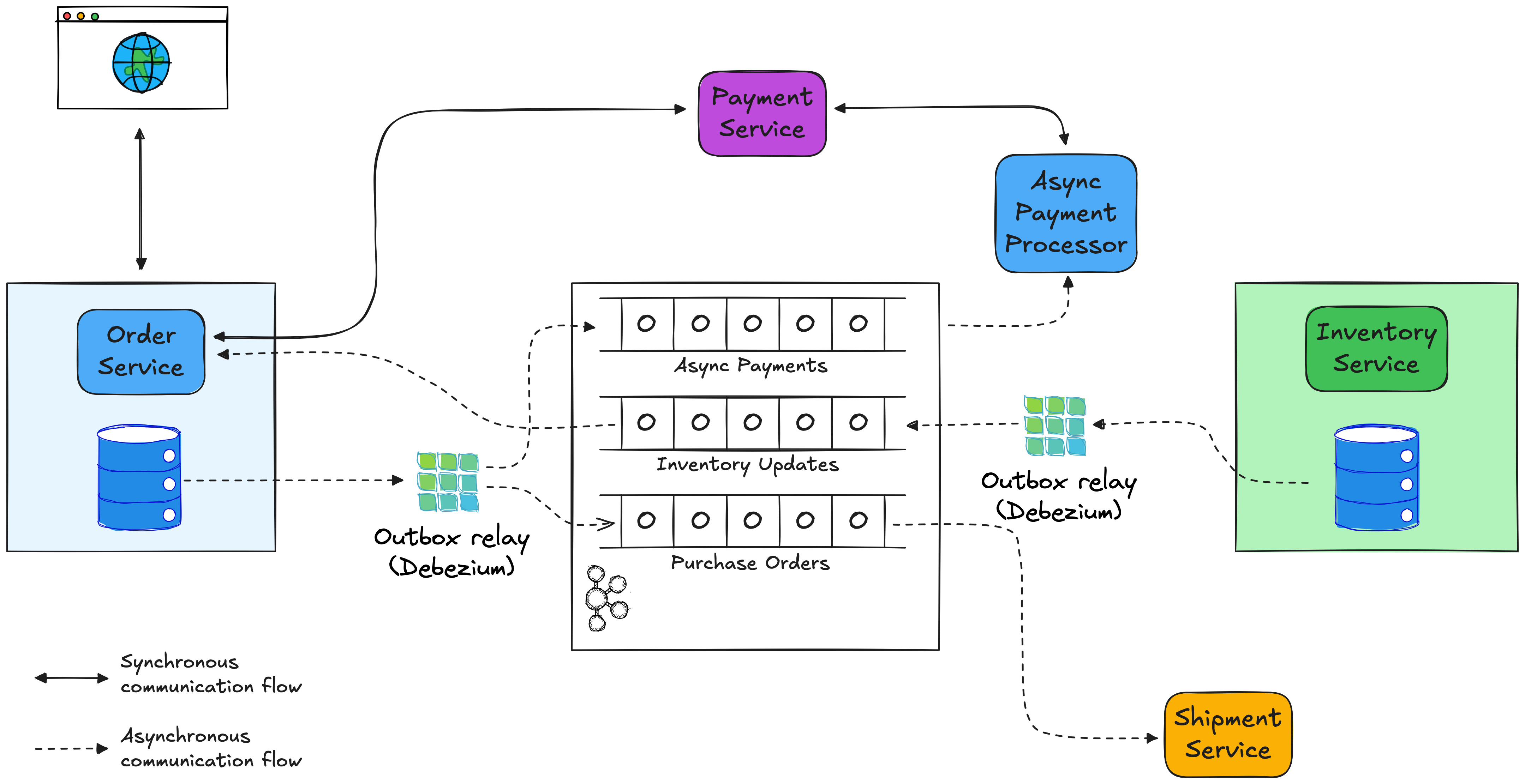

Let’s start with the last one, the shipment service. Does it matter to the customer who is placing an order when exactly the shipment service receives that notification? Not at all. Hence, notifying the shipment service synchronously from within the order entry request handler would be a waste of our synchrony budget. Not only would it cause that inbound request to take longer than it has to, it would also cause the order entry request to fail when the shipment service isn’t available, for instance due to maintenance, a network split, or some other kind of failure. Also, we don’t need to report any response from the shipment service back to the client making the inbound order placement request. This makes this call a perfect candidate for asynchronous execution, for instance by having the order service send a message to a Kafka topic, which then gets consumed by the shipment service. That way, the order service request isn’t slowed down by awaiting a response from the shipment service, also a downtime of the shipment service won’t affect the order service’s availability. It will just process any pending messages from the Kafka topic when it is up again. In general, whenever one service solely needs to notify another service about something that happened, defaulting to asynchronous communication makes a lot of sense.

In a similar spirit, if any changed data should be propagated from an OLTP data store to an OLAP system, this should be done asynchronously. By definition, analytical queries issued against the latter don’t require instantaneous visibility into each single data change as it is occurring in the OLTP system. So sending synchronous requests to an OLAP store would be another good example for unnecessarily spending your synchrony budget.

Now, what if our messaging infrastructure, such as Kafka, can’t be reached? Aren’t we back to square one? We might envision some means of buffering for that case, such as storing the messages to be sent in some local state store and sending them out once connectivity to Kafka has been restored. Luckily, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel here: the outbox pattern is a well-established approach for channeling outgoing messages through a service’s data store, transactionally consistent with any other data changes that need to be done at the same time. Tools for log-based change data capture (CDC), such as Debezium, can be used for extracting the messages from an outbox table with low overhead and high performance. That way, the only stateful resource which is required by a service to process incoming requests is its own database.

Let’s look at the communication with the inventory service next. When the order service processes an incoming request, it will require the information whether the specified item is available in the desired quantity. This differs from the notification semantics used for communicating with the shipment service, as we do need data from the inventory service in order to process the inbound request. So should we make a synchronous call in this case? It certainly could be an option, but again it would eat into our synchrony budget: there’d be an impact on our response times, and what should we do in case the inventory service isn’t available? Should the incoming request be failed? But not accepting customer requests because of some internal technical hick-up doesn’t sound that desirable.

Reversing the communication flow can be a way out: the inventory service could publish a feed of inventory changes, pushing a message to Kafka whenever there’s an inventory update. The order service could subscribe to this feed and materialize a view of this data in its own local data store. That way, no synchronous calls between services are required when processing an order request, this can solely be done by querying the order service’s database. The change feed of the inventory service could again be implemented via the outbox pattern; another option would be to use CDC for capturing changes in the actual business tables in the inventory database and then leverage stream processing, for instance with Apache Flink, to establish a stable data contract for that data stream. That way, consumers like the order service are shielded from any potentially disruptive changes to the shipment service’s data model and the stream processor can handle denormalizing relational tables to provide consumers with fully contextualized events.

Of course, there is a trade-off here: as updates to the order service’s view of the inventory data happen asynchronously, we might run into a situation where that view is outdated and a request for an item gets accepted, while it actually is not in stock any more. In practice, Debezium and Kafka can propagate data changes with sub-second latency end-to-end, so the time window for errors will be very small during normal operation. But it also helps to take a step back and look at things from a business perspective: reality isn’t transactional to begin with. I remember a birthday party a few years back where one of my friends was on call and had to patch the inventory table of an e-commerce application after a rack of flowers had been tossed over in the warehouse. In other words, a business needs to have means of dealing with situations like this in any case. In all likelihood, we’ll be better off sending a customer a $10 voucher as an apology in the rare case of accepting an order for an item without inventory, instead of spending our synchrony budget and establishing a synchronous call flow for this process.

Now, let’s look at the communication with the payment service. Depending on the specifics, this one actually may be a case where a synchronous call is justified. When for instance building a flight booking system, you really want to be 100% sure that the credit card of the customer can be charged successfully, before acknowledging a booking request. Replicating the data of all credit cards and bank accounts in the world obviously isn’t possible, so the call flow can’t be reversed either. It’s for a reason that payment processor APIs are built with extremely high availability in mind. And this is what the notion of the synchrony budget is about: implement inter-service calls asynchronously whenever it’s possible, so you have the room to make synchronous calls if and when it’s absolutely required. That being said, for an e-commerce application it may be actually feasible to make synchronous calls to the payment service by default, but fall back to asynchronous processing in case of failures. As the contract to sell typically only gets accepted when an item gets shipped, you still have the room to cancel an order if a payment falls through on the asynchronous processing path.

Finally, here’s how our overall solution of the data flows relevant to the order service could look like, applying the mental model of a synchrony budget: